The critical question that initiated the discourse on femininity and women in Khasi matrilineal society was, does the term ‘woman’ or ‘women’ as a sign signify a meaning different in their society, when juxtaposed to other patrilineal societies? Is the sign (woman) truly perceived different with no threat of shared conventions? The myth of patriarchy has been unravelled by Western feminist scholars, as a play of “gender politics”.The objective is to interrogate, re-examine and critique the constructed conventions of “women” in matrilineal societies and how folklore plays a vital role in mythologizing the institution as an ideal system. The Khasi’s are a tribal community of Meghalaya, North East India. They inhabit the central plateau along with the Synteng community of Jaintia hill and Garo community of Garo Hills of Meghalaya.The community is located amidst dense evergreen forest cover, magnificent waterfalls, sacred grove forest, and marvellous natural root bridges. It receives the highest rain fall and has abundance of other natural resources. What makes this community unique is that it follows a matrilineal system, which implies that the descent is traced through the mother’s womb and additionally, the maternal uncle plays a crucial role in the domestic space.

The central focus is to investigate whether the Khasi women are truly in the seat of authority and are willingly accepted by all men in the community without gender biasness. Partricia Mukhim in her article titled, “Khasi-PnarMatriliny: Reclaiming lost spaces”, observes, “Khasi women became custodians of their race when men had to go to war…life had become precarious for men so they decided to make the women the keepers of the family name and sequentially the society’s values”. What is perceived from the aforementioned observation is that, the origin of the matrilineal society was accorded by the man, “syiem”; men empowered women. Politics therefore, was already in the custody of men and, is still at present a male dominated profession. According to the myth men only granted women reign over the domestic politics which included only inheritance and kinship, while the men themselves retained control of the law making bodies outside the domestic space such as legislature, executive and judiciary. The law making bodies are dependent on the “Seng Khasi” which is the indigenous institution that governs Khasi law. The institution thus, functions as a signifier that produces meaning to the sign (woman).

The questions thus rises that are women truly empowered? In literature and journalism the matrilineal identity is fed to the public; especially to those outside the endogamy community; as a true reality. In an Aljazeera article written by Subir Bhumik, titled “Meghalaya: where women call the shots” he claims, “Many Indian women cry out for equality, but a matriarchal culture thrives with little parallel in the north east…..In India, where women often become victims of “honour killing” if seen with a male from another caste, Khasi-Jaintia women enjoy remarkable social mobility and can accompany any man without taboo. Unlike elsewhere in India where the bride’s family is generally required to pay a dowry to the groom’s family, the women of Khasi-Jaintia society do not. Nor is there any concept of arranged marriage.” The language employed by the journalist is that of a structured binary, and it asserts that if the Khasi are not patrilineal then they are for women’s rights. The writing sets a tone of idealism and portrays the community as an exotic alternative to patrilineal societies, without further investigation into the multiple layers of contradictions and complexities within the Khasi kinship system. The scholar P. R. T Gurdon in his book “the Khasis” prescribes to a writing style similar to that of a structured language. To the author, the Khasi women are blessed gods while the men are the victims. Referring to Roland Barthes seminary work such as, “The death of the Author” and “The Pleasure of the Text” the interstitial spaces and cross examination by the author P.R.T Gurdon is never undertaken.

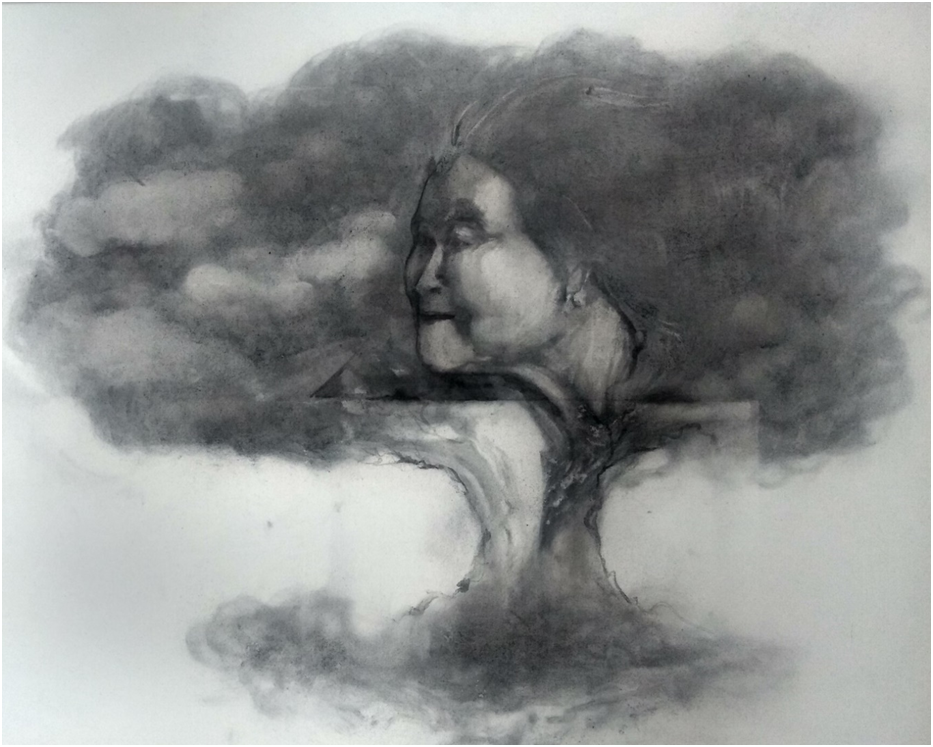

The visual culture consciously glorifies the matrilineal identity evident in the folklore, privileging its myth as the absolute truth. The painting by Benedict Skhemlang Hynniewta titled, “The Offering”, represents an intentional detachment from the male fantasy, the woman nudes, sexuality and politics of the gaze. The subversion of the sexual gaze is a conscious intention that denies the gazer the privilege of the objective fetishism on the community women. It is evident within the painting that women as a sign are those who are loyal to the family, husband and caring to the children, the one who provides for the family and performs her domestic duties. She is responsible for religious rituals within the domestic space and a willing obedience to her matrilineal duties that are also a set definition provided by the folklore and mythologies itself. Careen J. Langstieh’s painting series “kaiing” is important in relation to this context, bringing in a woman’s perspective the artist highlights the burdened responsibilities weighted down on women but also at the same time, how the women accept their eventual fate and they do so with joy and vigorous strength. The constructed forms within the painting express the very nature of this duality. The artist Careen Langstieh states, “As exotic as it may seem to belong to a matrilineal society to the outside world, it also bears huge responsibilities for the one who has to live in it”.

The Khasi’s have always been in the belief that their system of kinship functions opposite to patrilineal India. Feminism movement in the Indian state witnesses several monumental changes initiated at a political level as well as by private organizations on the issue of women. In the year 1903 and simultaneously in 1909 and 1912 issues of widow re-marriage, education, and Sati was debated at a National Conference. Woman participation in male dominated spaces such as journalism and literature was increasing and the field of fine arts opened up to the new emerging and aspiring women artist. The colleges of art that invested in the creative expression of women witnessed fruitful products such as Nilima Sheikh, Nalini Malani and Arpita Singh to name a few. However, this feminism movement had no significant impact on the Khasi-Jaintia state because the community belief that they already have in place, holds a system that protects women’s rights.

The advent of Christianity and the post-modern attitude has greatly impacted the matrilineal identity among the Khasi’s. The Kinship instead, has become a nominal system of property rights and lineage. Friction among the genders however, still persist; men demanding their right to ownership of land for business, fathers protesting against his nominal role in his wife’s household and women both eldest and the youngest burdened by the role of responsibilities. Additionally, both men and women are choosing to marry outside the endogamy community thus, infringing a threat to the matrilineal order. This new wave of liberalism seeks to devalue the matrilineal order and threatens the man’s right to a share in the property and business entrepreneurship through marriage. The conservative Khasi would probably identify this phenomenon as a plague and thus, to counter the problem, they sought to restore men’s rights through legislation which at present is still a male dominated profession. Convening on a drafted law, it states that a “Khasi woman” will be denied the right to property and inheritance if she chooses to marry outside the endogamy community. The irony is that the law applies only to the women and not men. This form of phallic control is decorated and justified as a form of protection.

Written by: Afreen Kraipak Khyriem,

Graduate and Post-Graduate in Art History

Artist: Benedict SkhemlangHynniewta

Title: The Offering

Medium: Acrylic on canvas

Size: 30×36 inches

Year: 2007

Copyrights: artist

Location: Meghalaya, Shillong

Artist: Careen J. Langstieh

Title: Kaiing series, I

Medium: Charcoal on canvas

Size: 24×30 inches

Year: 2019

Copyrights: artist, Location: Meghalaya, Shillong

Title: Kaiing II

title: Kaiing III

Reference

- Gurdon, P.R.T, “The Khasis”, Cosmo Publications, Gurdon, P.R.T, 1907

- Mukhim, Patricia, “Khasi-PnarMatriliny: Reclaiming lost spaces”, article

- Bhumik, Subir, “Meghalaya: where women call the shots”, Aljazeera article, 2013

- Pollock, Griselda; “Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and the histories of art”, Routledge Classics, 2003

- Sinha, Gayatri; “Expressions and Evocations- Contemporary women Artist in India”;Marg Publications, 2008